Face Clustering II: Neural Networks and K-Means

September 14, 2018

This is part two of a mini series. You can find part one here: Face Clustering with Python.

I coded my first neural network in 1998 or so… literally last century. I published my first paper on the subject in 2002 in a proper peer-reviewed publication and got a free trip to Hawaii for my troubles. Then, a few years later, after a couple more papers, I gave up my doctorate and went to work in industry. Maybe I’m more engineer than scientist. Maybe I prefer building stuff than theorising about stuff. Maybe… anyway…

Neural Networks back then were small and they took a while to train effectively. Some people (even me!) built some cool stuff with them, but their use-cases were limited. The idea that you could use them to recognise a person was, frankly, laughable back then. Sixteen years later we have The Cloud and compute resource is as cheap as… well… chips. Things have changed!

In the last article in this series I looked into an algorithmic approach to clustering/grouping faces based on various feature measurements: size of nose, distance between eyes etc. I had some very minor success, but in the end I fell foul of facial expressions. Turns out, people change the size and position of their facial features to communicate and express emotion. Who knew!?

A Better Embedding

Where I went wrong, with my brute force approach, was in the way I generated an embedding from my face images. Transforming source bitmap data into a numeric vector simply by measuring parts of the face is no good if people smile, or frown, or move.

As with all things, people have already solved this problem. They did this using all the CV enhancing buzz-words in the world Neural Networks and Deep Learning in the Cloud. Back in my youth, the idea that you’d build a neural net with thousands of inputs and 20-odd layers of several hundred nodes was just bonkers - but these days it’s fine. The term “Deep Learning” is simply a nod to this new freedom to train massive networks relatively cheaply.

A host of industry and academic experts have been training neural networks to recognise faces for some years. The really clever bit for me is that they aren’t directly training the neural networks to recognise specific people - they are training them to create better embeddings.

It turns out that there are several, freely available, pre-trained neural nets available for download which have been taught to output distinct embeddings for any given face. So the array of values these networks output given a picture of me, will be different to the vector they produce for my wife, or my daughters. Two photos of my eldest will produce embeddings more similar to each other than to those from a photo of my wife.

Clustering with Neural Embeddings

Yet again, using Python and the work of chap called face_recognition library wraps a pre-trained face recognition network. Here’s the sum total of the code I had to write to use it:

import face_recognition

class NeuralFeatureDetector:

def process_file(self, filename):

image = face_recognition.load_image_file(filename)

encodings = face_recognition.face_encodings(image)

print("Generated {0} encodings".format(len(encodings)))

for encoding in encodings:

# Return the feature data

face_data = {

"filename": "faces/" + filename.split('/')[-1],

"features": encoding.tolist()

}

yield face_data

I wrapped the strategy for creating an embedding in a class so I could swap out the “Old School” strategy from the previous article. The code loads the image, gets the embeddings and returns them wrapped up with the filename. That’s it. Easy!

Well, that worked a bit better than last time, didn’t it! There is literally only one error visible in that image: the appearance of a stranger on the last row with yours truly.

Stranger Danger

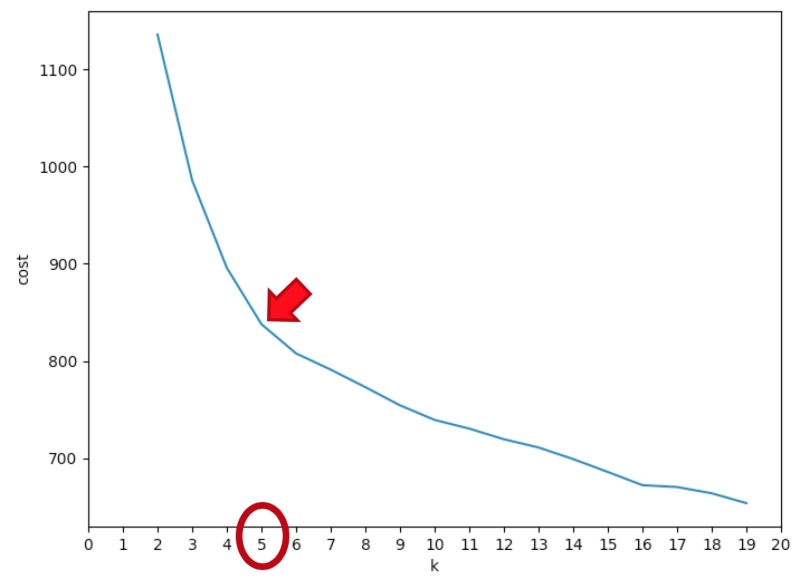

The code I wrote to find faces in our holiday photos simply trawls through each image and grabs any face it finds. Inevitably some unknown folks were caught in the background of some of the pictures we took. Basically, my assumption that there would be four clusters in the input data was wrong - and this is supported by the k-means cost function:

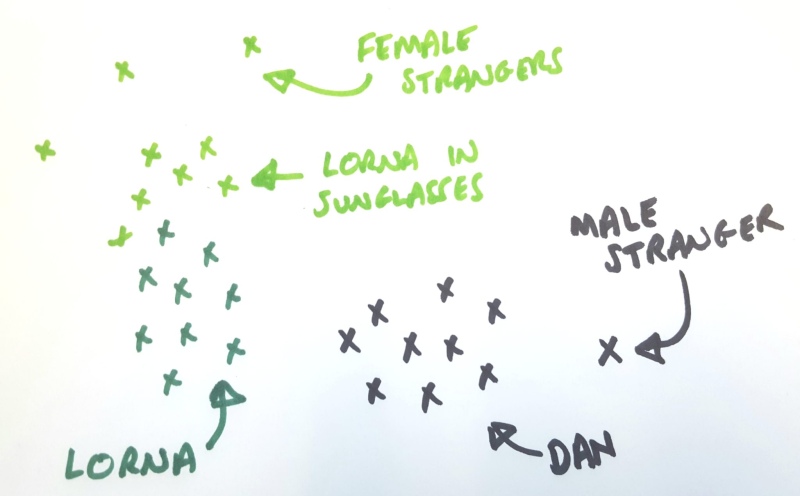

So, I changed to k=5 to see what happened. The results were initially a bit confusing. The addition of a 5th group didn’t separate the Strangers from the Taylors - or at least not in the way I expected:

The first four clusters look OK. There’s a row for my wife, one each for my two lovely daughters and one for me… but then on the last row there’s a mixture of strangers and my wife and daughter in sun glasses! That’s not what I’d expected at all!

Precision, Recall and False Positives

So is k=5 worse than k=4? Did the “cluster of strangers” plan fail? Well, that depends!

With a lot of machine learning algorithms, you need to think about whether you care more about False Positives or False Negatives. Depending on the use case, you might need to say “I am certain that this is a photo of Dan” or alternatively “these are all the photos I think contain Dan”.

My clustering attempt with k=5 lowered my false positive rate, increasing my recall. That is, the first four clusters were now almost 100% correct: the rate of false positives was low. The 5th cluster, however, contained a mixture of strangers (true negatives - a good thing) and family members (false negatives - a bad thing). If I wanted to be sure that every photo is who I think it is, I might have been happy with this.

In the k=4 example, the recall was higher - there were more photos of each of us in our respective clusters, but the number of false positives was also higher - the precision was lower. If I was searching CCTV for potential sightings of a master criminal, I might well opt for this alternative as it increases the chances of finding who I’m looking for and I could easily filter the false negatives manually.

Where k=5 there is in fact only one false positive in the whole dataset - this guy here, who my algorithm thinks is me.

Why it’s Hard to Cluster Strangers

So why didn’t K-Means make a cluster of strangers as we expected it to? The answer to this is not that it was unable to differentiate between the Strangers and the Taylors - it actually comes back to the similarity theory that started this whole journey.

Simply put, the male stranger looks more like me than he does the female strangers. In the picture above, I’ve sketched out how I see this happening (projected down to 2D space!). The male stranger is clearly different to me - he’s a fair distance away from the points which correspond to the photos of my face. Likewise, the female strangers are separated from the photos of Lorna (who is my wife, by the way) but they are closer to the photos of her in sunglasses. When K-Means tries to group these points together, the male stranger and I share a group, and the female strangers go with the bespectacled Lorna.

K-Means is not very good at dealing with outliers! Also, it is a very naive clustering algorithm - it’s not learning anything about my family, it’s just clustering similar points.

Another Look at Similarity

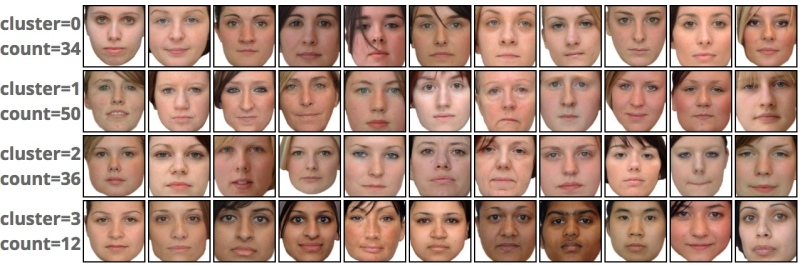

Given that this all started with a theory on similarity, before I close out this post, I thought I should at least share the results of the Neural Clustering on the Unfamiliar Faces. I’m going to present them without comment - you can make your own mind up on which one is better and whether either does a good job…

Remember, the original challenge was to group similar looking people on each row…

So What?

So when it comes to recognising family members and clustering them together, I think I’ve proved that neural network generated embeddings are the way to go. Who knows what features of our faces they are looking at to create the vector of weird numbers, but they are undoubtedly coping better with the facial expressions and differing camera angles than the direct measurement approach.

The downside of neural networks is exactly this uncertainty. How did they generate those embeddings? How do they rank nose size versus eye separation in terms of importance? In a world where we need to explain why the faces are grouped the way they are, neural nets are not so great. But realistically, when would that be important in real life?

Thanks for sticking around to the end of Part 2. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did!